Part 4—Beyond the Stages: Holding Grief and Life at the Same Time

Grief does not move in straight lines. In this final part of Beyond the Stages, I reflect on the framework that helped me hold loss and life at the same time, and why a squiggly line became the most honest way to understand grief.

In seasons when grief feels collective and the world feels heavy, I find myself returning to the same question I once asked as a researcher: how do the ones left behind survive while holding loss? Right now...in this moment, grief feels close to the surface, whether personal or shared, and I am reminded that loss does not arrive politely or follow a schedule. It interrupts. It lingers. It coexists with ordinary life in ways that feel confusing and, at times, unbearable. I needed to acknowledge this truth, and the way this work has met me in this moment, before turning to Part 4 of Beyond the Stages.

In Parts 1 through 3, I traced my search for a lens through which I could better understand the grief experiences of African Americans who had lost a pet. As both a researcher and a person acquainted with grief, I needed a framework that did not try to make sense of grief by forcing it into order. I needed one that reflected how grief actually lives in the body and unfolds in daily life.

What ultimately helped me understand grief was not a stage or a task.

〰️It was a squiggly line.〰️

Oscillation, or “The Squiggly Line”

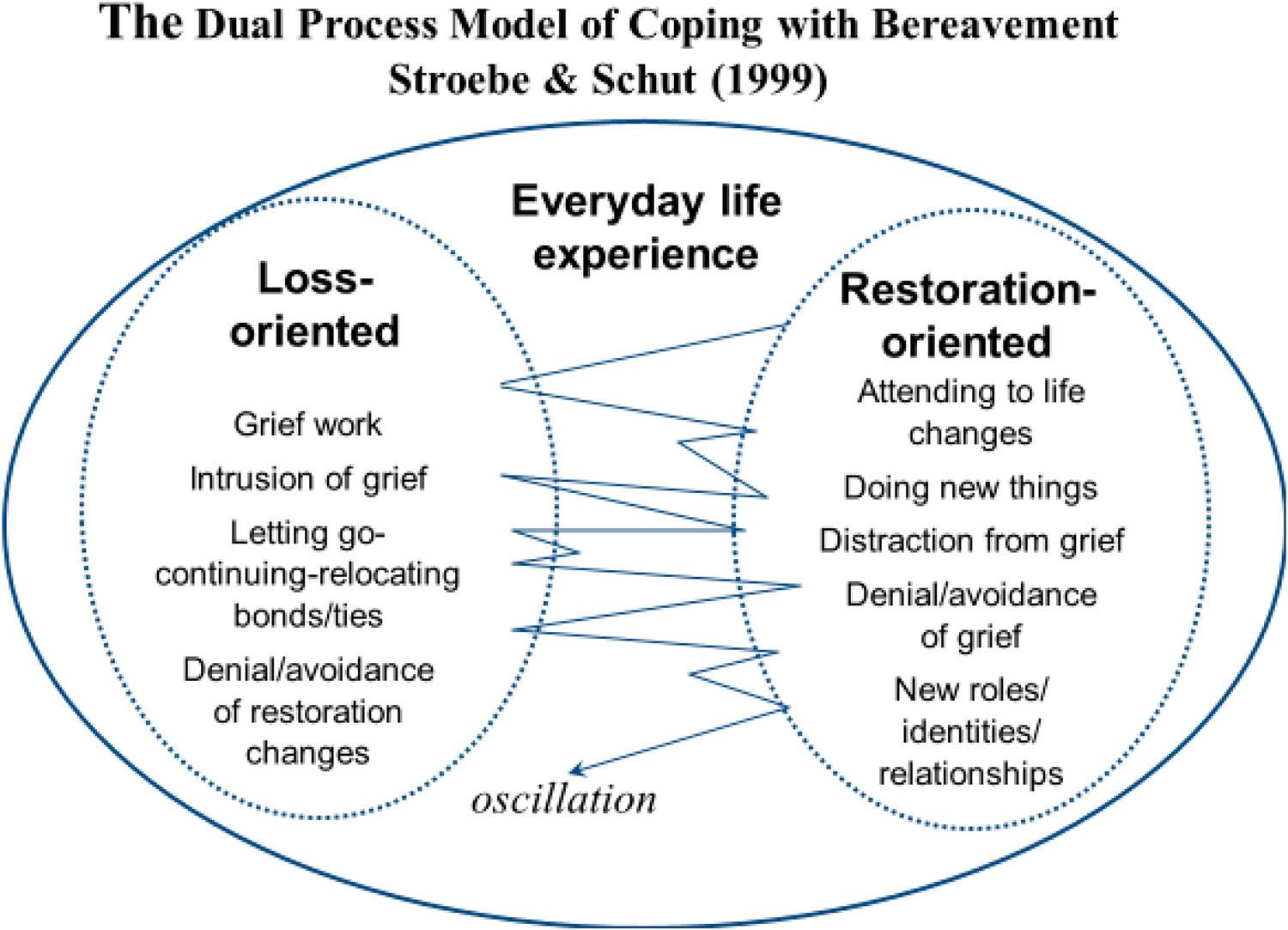

In the Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement (DPM), developed by Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut (1999), the squiggly line represents a concept known as oscillation. Through oscillation, grief moves dynamically back and forth between two orientations: loss-oriented coping and restoration-oriented coping. At first glance, this may seem simple. In reality, it became the key to understanding grief in the context of my research.

Previous grief theories and models focused primarily on grief work, emphasizing the confrontation of loss and the processing of emotions. What these models often neglected was adaptation to the loss, or how people continue living, reorganize their lives, and form new identities while still grieving (Stroebe & Schut, 1999; Stroebe & Schut, 2010).

The Dual Process Model includes both grief work and adaptation within the same framework. It does not ask people to choose between grieving and living. Instead, it assumes they will do both, moving back and forth rather than toward a single point of resolution.

Loss, Restoration, and the Space Between

The Dual Process Model involves two forms of coping that exist in relationship to one another. Loss-oriented coping focuses on confronting the loss itself. This includes grief work, continuing bonds, and moments of deep emotional pain. Restoration-oriented coping, by contrast, involves attending to life changes, developing new roles or routines, engaging in distraction, and rebuilding a sense of identity in the absence of the deceased (Stroebe & Schut, 1999; Stroebe & Schut, 2001).

What mattered most to me, both in my research and in reflecting on my own losses, was that neither orientation was framed as better or more “healthy” than the other. Grief was not something to complete. Restoration was not betrayal. And moving between the two was not avoidance or failure. It was the journey.

As I was writing the framework section of my dissertation proposal, I realized something I had not fully named before. Nearly thirty years had passed since my sister was murdered, and yet I had never truly sat with that loss as something to be confronted and integrated. Life had moved forward, and in many ways I had adapted. But I could not say that the healthiest form of adaptation had occurred, at least not in the way the Dual Process Model describes.

Writing about grief brought me face-to-face with everything that was still there. Memories. Emotions. Unanswered questions. In that moment, I was engaging with the loss not as a distant fact, but as something still living within me. I was no longer a teenager surviving shock. I was an adult shaped by years of experience, faith, and reflection. At the same time, I could see how my life had been restored through perseverance, resilience, and forward movement, even without conscious processing of that loss.

The Dual Process Model gave language to a complex experience I had lived without understanding. It helped me see that adaptation does not erase loss, and confrontation does not undo survival. The oscillation itself was the work.

People move back and forth. They grieve deeply one day and function the next. They feel okay for a moment and then feel undone again. The Dual Process Model normalizes this movement and names it as part of meaning-making rather than pathology.

〰️That squiggly line allowed grief to breathe.〰️

Why This Framework Fit My Research

The central research question of my study was to understand how African Americans grieve the loss of a pet. The Dual Process Model offered a way to approach that question without minimizing grief or forcing it into a culturally narrow definition of “healthy coping.”

Grief processes vary across cultures. They are shaped by coping strategies, by whether individuals lean toward loss-oriented or restoration-oriented coping, and by how those orientations interact over time. The Dual Process Model allowed me to attend to the cultural context of pet loss, including how the death of a pet is perceived, mourned, and sometimes dismissed by others.

For African Americans, pet loss may be deeply meaningful while simultaneously being socially minimized or stigmatized. In my research, this grief often unfolded alongside broader inequities, including limited access to post-loss social support, cumulative human and animal losses, and the disproportionate burden of grief during the COVID-19 pandemic. Work constraints, financial pressures, and the circumstances surrounding a pet’s death further shaped how grief was experienced and managed.

The Dual Process Model provided a framework for understanding how individuals hold this tension while navigating emotional responses, continuing bonds, and the social and interpersonal contexts of grief.

It did not require grief to look a certain way.

Culture, Faith, and Oscillation

One of the reasons the Dual Process Model resonated so deeply with me is that oscillation already exists within many African American cultural and spiritual practices. There is space for lament and praise, for sorrow and resilience, and for silence and testimony. Faith does not remove grief; it gives language for living with mystery.

The movement between loss and restoration mirrors how many people survive difficult realities. Community care often functions as restoration-oriented coping, while quiet remembrance may reflect loss-oriented coping. Neither cancels the other, and neither is a failure.

The Dual Process Model made room for that truth.

How the Framework Shaped My Study

Using the Dual Process Model informed both my research design and the development of interview questions for participants. Loss-oriented coping was reflected in questions about participants’ initial reactions to their pet’s death, ongoing emotional connections, and meaning-making. Restoration-oriented coping guided questions about daily routines, social relationships, and navigating life after loss.

Oscillation helped me listen differently. It allowed me to hear contradiction without trying to resolve it and made space for grief and growth to exist side by side.

Studies applying the Dual Process Model across various forms of bereavement, including spousal loss, parental loss, and pet loss, demonstrate the importance of both individual coping strategies and social support networks in facilitating adjustment (Packman et al., 2014; Habarth et al., 2017; Stroebe & Schut, 2010; Whitney, 2025).

What mattered most was that the framework did not flatten experience. It honored complexity.

Why I Chose the Squiggly Line

It may seem counterintuitive to seek a model for something as personal and unpredictable as grief. But I was not searching for certainty. I was searching for a squiggly line.

One that allowed for movement back and forth. For grieving and living to coexist. For honoring the mysteries of life and death without needing to resolve them.

There are many frameworks and theories of grief, both foundational and contemporary, that may resonate depending on the work being done. There are also empirical and practical critiques that can be made of any model, including this one. But for me, the Dual Process Model became more than a framework for my study. It continues to shape how I understand loss, faith, and the rhythms of being human.

〰️ Sometimes the most honest path is not a straight line, but a squiggly one. 〰️

References

Habarth, J., Bussolari, C., Gomez, R., Carmack, B. J., Ronen, R., Field, N. P., & Packman, W. (2017). Continuing bonds and psychosocial functioning in a

recently bereaved pet loss sample. Anthrozoos, 30(4), 651–670.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2017.1370242

Packman, W., Carmack, B. J., Katz, R., Carlos, F., Field, N. P., & Landers, C. (2014). Online survey as empathic bridging for the disenfranchised grief of pet loss. Omega - Journal of Death And Dying, 69(4), 333–356.

https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.69.4.a

Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23(3), 197–224.

https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201046

Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (2010). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: A decade on. Omega - Journal of Death & Dying, 61(4), 273–289.

https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.61.4.b

Whitney, M. L. (2025). Understanding Grief Experiences of Pet Loss Among African Americans (Doctoral dissertation, Walden University).