The Why Behind the Work: Reflecting on a Summer of Sharing My Research

I've just wrapped up an unexpected summer tour of my dissertation research. As I reflect on this whirlwind of posters, presentations, and first-time academic conference navigation, I keep getting asked the same question: "Why this research?"

Sometimes the most important research questions emerge not from what we're looking for, but from what we notice is missing.

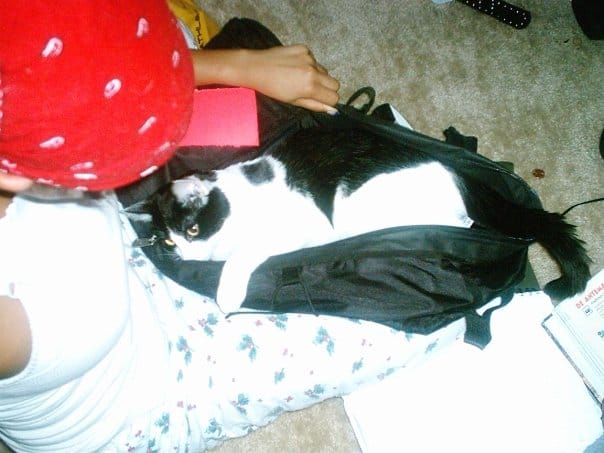

When Family Included Four Paws

Other than being inspired by my cat Samson, particularly in the early years of our bond, I became fascinated with the family aspect. I curiously observed my own attachment to him, as well as his role in our whole family. To me, he was my son. To my mom, he was grandcat. To my nieces, he was cousin. Our whole anthropomorphic way of relating to him as a family, which some might consider neurotic, but we considered uniquely Samson, made him part of our lives in ways that felt completely natural to us.

The fascination with my own relationship with Samson intersected with the family-Samson dynamic, and this inspired me to begin an academic project back in the 2010s that involved an exhaustive review of human-animal bond research. What I discovered was a glaring gap: the majority of studies included homogeneously White and female samples. This tendency to focus on these types of samples only reflected one truth, not the full spectrum of human-animal relationships.

I wasn't alone in this discovery; researchers noticed it too. For example, in a 2006 study called "The Animal-Human Bond and Ethnic Diversity" by Arizona State University researchers Dr. Christina Risley-Curtiss, Dr. Lynn Holley, and Shapard Wolf, examined relationships between race and ethnicity, and beliefs about pets and pet ownership. They suggested that more quantitative and qualitative studies were needed that examined race and ethnicity in relation to the human-animal bond—a significant gap in the research (Risley-Curtiss et al., 2006).

Despite these insights, for various reasons, I had to put my human-animal bond project on the shelf. However, I dusted it off again in 2021 when I began working on my PhD.

A Gap That Wouldn't Close

What I discovered in the time between shelving the old project and beginning the new one was striking: in the years that I hadn't looked at any human-animal bond research, not much had changed. By this time, COVID was life, and there was important research about the human-animal bond being done with COVID as a factor. I had an opportunity to attend a virtual conference focused on human-animal bond studies, where many of the presented studies incorporated a COVID aspect. But despite the critical work being done, the samples were the same, and the fact that they were the same was glossed over as if it were a limitation to be accepted.

Additionally, as we were all staying in place during that time, there was extensive media coverage about pets and the benefits of pet ownership. And while I agreed that pet ownership was beneficial, I couldn't help but feel conflicted. I had just put Samson down in January 2020 and was lucky enough to adopt my cats, Tina and Joe, shortly after. But what if I hadn't been able to adopt them? What about the broader family context? I thought to myself: yes, pet ownership has positive aspects, but are we really taking a holistic look at the experience?

I felt at that time, more than ever, that the human-animal bond as a research discipline needed something more.

The Other Side of the Story

At the same time that the benefits of pets were front and center, there was also the seemingly glaring "discovery" that COVID was disproportionately impacting the African American community (Yancy, 2020). I began thinking about the gap between a few things: African Americans and disproportionate grief, what happens in households that have to deal with systemic issues, and reconciling all of these realities. Going out and getting a dog or a cat is not the answer to systemic problems.

I reflected on my own journey. Single and childless and separated from the little family I had because of Covid...but for adopting Tina and Joe shortly after losing Samson, I would have been in the house alone with nothing to care for. What would have been the mental and emotional impact?

There was more than one side to this story, and social science needed to be informed.

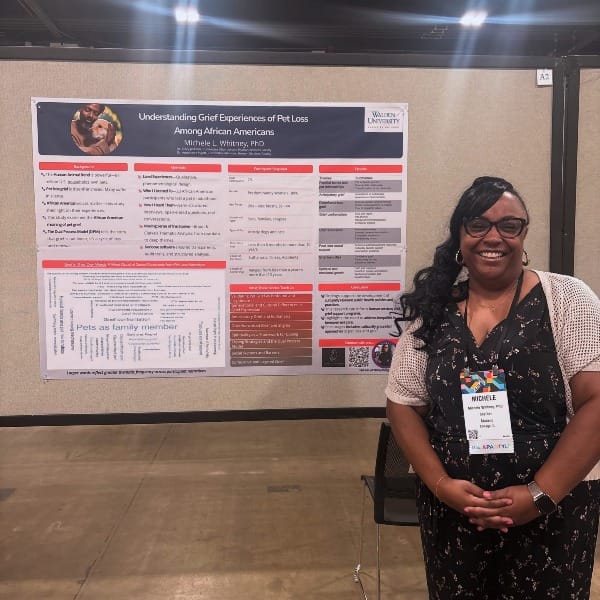

My experience as an African American woman who had experienced pet loss as an adult intersected with a gap in knowledge, and "Understanding Grief Experiences of Pet Loss Among African Americans" was born.

Facing the Side Eyes

As I've toured my little research idea this summer, I've received support, but also got the side eye sometimes, or a few confused looks. Some because of the race aspect—I had one individual tell me (and in all fairness, this person was not from the United States) that if they had done a research study like mine, it would have been considered racist. Through which I confidently educated them on the unique experiences and culture of African Americans in the United States, a group of individuals who were forced out of their original culture into a culture they had to make their own in a country that hated them. So in this case, the race aspect was about context, not prejudice.

Some gave me the side eye because of the pet loss aspect, passing by my poster at conferences, saying, "This is going to make me cry," or "I don't want to think about this." Some of these comments came from people involved in human-animal studies. I get it, but at the end of the day, unless something out of order happens, we will outlive our pets. And I've learned this loss experience can extend to therapy and emotional support animals, through death or retirement. And as adults, we may outlive our pets multiple times if we choose to give love again after loss.

The Beginning, Not the End

Overall, it has been an amazing summer filled with learning how to do this academic thing for the first time, like figuring out how to do posters and just doing stuff (like going to Milan!) and not knowing what the heck I was doing. 😅 And through all of that: making connections, seeing lightbulbs go off, nodding heads, people providing me with encouragement, compassionate feedback, and requesting collaborations.

It is a summer I will never forget, and I'm forever grateful for it.

This is only the beginning. I think. 😉 😺

Listen to more about my human-animal bond journey in Exploring the Human-Animal Bond with Dr. Michele Whitney (Part 1) on the Resilient Animal Podcast with Dr. Annie Petersen.

References

Risley-Curtiss, C., Holley, L. C., & Wolf, S. (2006). The animal-human bond and ethnic diversity. Social Work, 51(3), 257-268.

Yancy, C. W. (2020). COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA, 323(19), 1891-1892. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6548